The unintended consequences of the conflict go far, especially in the global IT sector.

A war’s effects spread further than the conflict itself. While some repercussions can be reasonably predicted, others cannot.

Our close observation of the war in Ukraine has revealed some of these unexpected consequences on the global threat landscape. These tend to stem from the effects of the war in Russia itself. In this article we examine these and assess their impact — in particular on the global IT sector.

We consider the effect on:

- Russia’s domestic IT sectors from semiconductor import restrictions

- The global threat landscape

- Russia’s cyber and military capabilities

- International cybersecurity co-operation

Want to read more on this and other stories? Subscribe to our newsletter to access the complete Weekly Intelligence Snapshot. Don’t miss out on more intelligence!

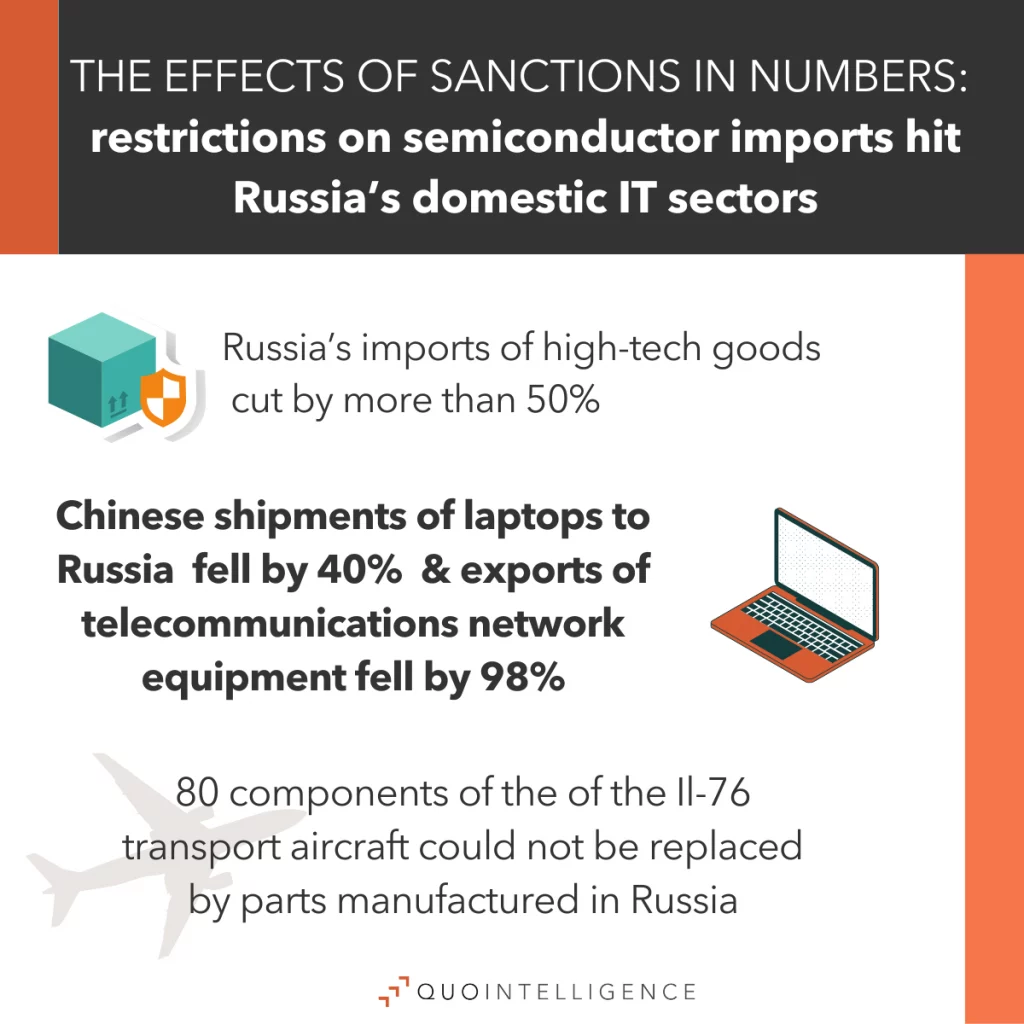

1. Sanctions: restrictions on semiconductor imports hit Russia’s domestic IT sectors

The war is having a profound effect on Russia’s domestic IT sectors. For example, sanctions on the Russian tech sector are depriving Russia of sophisticated semiconductors. In April, Western countries’ export controls cut Russia’s imports of high-tech goods by more than half, and left Russia short on semiconductors and struggling to find parts for its military. In addition, following Western sanctions on Russia, a considerable amount of Chinese tech companies are also stopping their business in Russia under pressure from US sanctions and suppliers. Among Chinese companies to halt shipments to Russia is Lenovo. Chinese shipments of laptops to Russia fell by 40 percent in March and exports of telecommunications network equipment fell 98 percent.

Sanctions related to the semiconductor industry pose a significant threat to Russian military capabilities, given the military’s reliance on foreign-produced electronic components for advanced weapon systems. According to the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), systems dependent on chip imports include: the 9M727 and Kh-101 cruise missiles, the TOR-M2 air-defense system and military radios R-168-5UN-2, R-168-5UN-1, R-168-5UT-2.

In terms of the effect on Russian cyber operations it is important to note that know-how and technical knowledge is not the only factor limiting Russian capabilities to replace imported semiconductors. The main issue is the lack of technical capability to manufacture elements domestically. According to reports obtained by Ukrainian intelligence, analysis of communication equipment of the Il-76 transport aircraft conducted by the Institute of Radio-Engineering and Electronics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, revealed that 80 components could not be replaced by parts manufactured in Russia.

Looking further ahead, given the expected long-term effects of sanctions, it is likely that Russian intelligence agencies will be tasked with collecting data to be able to at least partially develop home-grown technological capabilities in the long term.

But in the short term, turning to industrial espionage will not significantly improve Russia’s situation. This is further exacerbated by the fact that production of semiconductors is highly concentrated with only a few global companies controlling most of the production (explored in more detail later).

2. The Global Threat Landscape:

Outside the IT sector and given the financial impact of sanctions limiting access to wire transfer networks, it is likely Russia will try to alleviate the damage through ransomware payments. The US Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued a warning against attempts to use convertible virtual currency (CVC) for wire transfers to evade sanctions.

The question of whether Russia will use cryptocurrency to avoid sanctions through concealing the transfer of funds and supplementing income by deploying ransomware is multifaceted. In terms of the strategic situation of the Russian economy, it will not have a major influence as the volume of transactions that could be hidden this way is simply too low. Bitcoin, the cryptocurrency having highest market cap, has a daily volume of around USD 34 billion and total market cap of around USD 570 billion.

To compare, when the US imposed restrictions on transactions with Russian banks and major state companies, USD 1.4 trillion of assets were affected. Therefore, given the fact that transactions aiming to alleviate sanction effects would have to constitute a significant percentage of daily volume, they would be difficult to conceal from Anti Money Laundering (AML) and law enforcement monitoring.

That said, the lack of effectiveness does not necessarily mean efforts will not be undertaken. This stems from both the complicated relationship between Russian intelligence services, eCrime ransomware operators and the Russian state.

Russian intelligence services are known to have adversarial relationships with each other, with government entities having overlapping responsibilities and competing access to leadership. Therefore, intelligence agencies attempt to use ransomware operations to appeal to the leadership by appearing as providers of economic support to alleviate sanctions. Use of cyber operations as a source of income is comparable to North Korea, which conducts ransomware attacks and wire fraud to provide funds for the regime.

Autonomous eCrime groups and their relationship to the state

Using the model of state responsibility proposed by Jason Healey, ransomware actors operate somewhere between the level of state-ignored and state-encouraged activity.

The state-ignored part comes from the fact that operators, in general, are not prosecuted as long as they do not attack targets in Russia. As for the state-encouraged level, this comes mainly from the model of incentives that the Russian government grants eCrime groups, making it clear that attacks against foreign entities will be treated favorably by security services10.

The actual number of ransomware incidents has dropped – most likely due to difficulties in moving funds in the aftermath of sanctions. Going forward, this can play out in two ways. The first is criminal groups and private citizens trying to alleviate the effects of an economic downturn by engaging in criminal activity. This can be further encouraged with tacit agreement from the government that such activities will not be prosecuted (state-ignored).

Second, is the government’s use of eCrime groups as proxies to conduct activities described earlier – that is bottom-up initiatives of intelligence agencies attempting to provide funding. This scenario, however, is less likely, as using proxy actors introduces additional operational complexities such as controlling the scope and provides little additional benefit such as plausible deniability.

Russia’s cyber and military capabilities

In terms of military and cyber operations, sanctions again pose a problem for Russia’s advanced capability development and deployment. This is particularly true with military equipment, with Russia’s reliance on imported components making it vulnerable to import restrictions (see above). Lacking the capability to buy semiconductors from TSMC, Russia was forced to resort to using household electronic equipment components for military use. At the same time, it is almost certain that Russia will not be able to develop required manufacturing capabilities domestically.

Industrial espionage will not help

The most important aspect is lack of production facilities to design and manufacture advanced chips. Chip technology is most commonly described in terms of nanometers (nm), the lower the number the more advanced the technology. The measure does not refer to actual physical measurements of the components. It is a marketing term indicating a generation of the technology.

The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) plans to manufacturing e 2nm components by 2026. In contrast, Russia is aiming to at achieving 28nm production capabilities by 2030. Russian chip manufacturer, Mikron, is producing its Elbrus-4S chip in 65nm technology. On the other hand, three entities are currently capable of producing sub-10nm chips – TSMC, Samsung, and Intel.

Intel, AMD, and Samsung cut Russia’s access to such fabrication capabilities following Western sanctions.

And even further, Taiwan has imposed its own restrictions affecting essentially all modern chip designs. Restrictions affect fabrication equipment as well, undercutting not only contemporary supply but also attempts of developing domestic manufacturing capabilities. While the 65nm technology chips currently used in Russia can satisfy part of the needs, more advanced weaponry requires the import of components.

Taking into consideration shortages observed on the battlefield, and lagging technology production it is improbable that cyber operations aimed at industrial espionage will improve the situation in time to make a major difference to the war effort.

However, Russia will have to consider its lack of access to chip imports in the long term, which means having to catch up with domestic capabilities both in terms of fabrication as well as know-how. Operations aimed at capturing foreign-developed production methods, workflows, and best practices, support this need and reduce R&D spend. In 2018, The US National Counterintelligence and Security Center warned of Russian intelligence operations and industrial espionage in these areas, pointing out that cyber activity by APT28 dates back to 2007. Similarly in 2012, the FBI arrested a group which supplied commercially available high-tech components to Russia through a shell company. Given the current circumstances and pressure arising from diminishing military potential, it is probable that espionage efforts to collect semiconductor technology will increase.

IT personnel flight from Russia

Emigration of IT professionals will have an indirect impact on Russian cyber capabilities due to the reliance of private-public partnership support of state-sponsored operations.

The most glaring example is Positive Technologies, a company involved in advanced security research, which has been put on the US Department of Treasury sanction list due to connections with the FSB and GRU. As per Kim Zetter’s reporting, Positive is referred to in an Atlantic Council report as “ENFER” as an entity providing support to governmental offensive cyber operations. The report claims that ENFER supports Russian intelligence agencies with access capabilities, including direct tasking from the FSB.

Given the advanced capabilities provided by private sector companies in terms of reverse engineering, malware development, and vulnerability, the availability of research talent is likely to affect the pace of development of targeted implants.

Furthermore, according to the Atlantic council report, ENFER was not only involved in offensive R&D activities but also used penetration testing engagements as a method of discovering vulnerabilities and initial access methods that were later used during intelligence operations.

This is of course in addition to the shortage of IT personnel available for recruitment for military and intelligence agencies. In terms of the current effects on the operational tempo of state-sponsored activities, accurate assessment is not possible since knowledge of operation teams’ staffing is unknown.

Taking into consideration that supporting kinetic operations in Ukraine are numerous and widespread, and CISA warnings about further operations, it is assumed resources are adequate to cover the operational needs of Russian intelligence. However, the likely effects of personnel shortages will be more profound in the coming years.

International co-operation on cybersecurity

Let us finish on a positive note. Not all consequences of the conflict are negative. For example, many countries and organizations are now reviewing and enhancing their cybersecurity protection. At the same time, nations are reducing their reliance on Russian technology and services as they try to isolate the country with sanctions and protect themselves against potential threats.

At its latest meeting in May, the US-EU Technology Council focused on securing the semiconductor supply chain, promoting the use of trusted information and communications technology (ICT) suppliers, and tackling Russian disinformation. and came up with a raft of agreements and decisions. These included:

- Deeper information exchange on exports of critical US and EU technology, with a focus on Russia and other potential sanction evaders;

- The creation of a US-EU Strategic Standardization Information (SSI) mechanism to enable information sharing on international standards development;

- An early warning system to better predict and address potential semiconductor supply chain disruptions as well as a transatlantic approach to semiconductor investment aimed at ensuring security of supply and avoiding subsidy races;

- A dedicated task force to promote the use of trusted/non-high-risk ICT suppliers through financing for deployments in third countries;

- A new Cooperation Framework on issues related to information integrity in crises, with a focus on ongoing issues related to Russian aggression;

- A US-EU guide to cybersecurity best practices for small and medium-sized companies, whose business is impacted disproportionally by cyber threats.

Conclusion

Sanctions imposed on Russia have had, and continue to have wide ranging effects. While the economic ones are most obvious, in terms of the threat landscape there are important points to be aware of.

Russia suffers heavily from sanctions limiting its access to semiconductor manufacturers, directly impacting its war effort. Industrial espionage operations will have limited effect in alleviating this, as the problem lies with a lack of manufacturing capability that cannot be easily procured in the short term.

While cryptocurrency is very often mentioned as a mean to avoid the sanctions, the volume is simply too low to make an impact for the Russia’s economy. As such it is not expected that massive and coordinated ransomware attacks will be used to supplement income.

A shortage of IT workers could have effects on Russian cyber capabilities, both in terms of shortage of recruits and the weakening of private sector security research. The latter is significant given the support to state-sponsored cyber operations provided by private sector entities.

Overall, sanctions will likely not have a major short-term impact on the threat landscape related to operations originating from Russia. In the longer term, however, we can expect an increase of operational tempo related to espionage aimed at semiconductor technology, for the benefit of domestic industry. The impact of personnel shortage cannot be assessed at this time since current staffing in Russian intelligence agencies is unknown. A best estimate is that no immediate effect has been seen, based on the tempo of operational activities supporting the invasion of Ukraine.