This post is the first in a series of three blogposts. QuoIntelligence has been working on an extensive study of the participation of non-state actors in cyber operations or in the development of cyber capabilities on the behalf of Russia and China. These authoritarian regimes are increasingly leveraging private organizations, cybercriminals, hacktivist collectives to carry out espionage, conduct information operations, and disrupt adversaries. Our research explores the historical legacies, institutional architectures, and strategic cultures that have shaped the Russian and Chinese outsourcing models. By contrasting the opportunistic alliances between Russian intelligence services and eCrime or hacktivist groups with with China’s state-civil fusion approach, this study aims to shed light on the blurring boundaries between state and non-state cyber actors and what this means for attribution, deterrence, and the broader cyber threat landscape.

In terms of sources, this research draws on a diverse range of materials, including leaks, indictments, publications by Western intelligence agencies, academic research, and reporting from Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) vendors and cybersecurity firms.

The report is structured as follows:

- The first blog post offers a comprehensive overview of the Russian outsourcing model, tracing its historical evolution and outlining its key characteristics and actors. It concludes with a brief case study on the Doppelgänger information operation network.

- The second post will examine China’s externalization of cyber operations, focusing on the ties between the private and public sectors. It analyzes the role of China’s national strategy of state-civil fusion, supported by a robust regulatory framework that advances its cyber objectives. The post concludes with a case study on China’s approach to discovering and exploiting vulnerabilities.

- The final blog post will present a comparative analysis of the Russian and Chinese models, highlighting their key differences and similarities, and offering insights and implications for the CTI community.

Key Insights:

- Russia’s hybrid cyber model—merging state strategy with non-state execution—sustains its asymmetric advantage and reinforces its position as a leading global cyber actor.

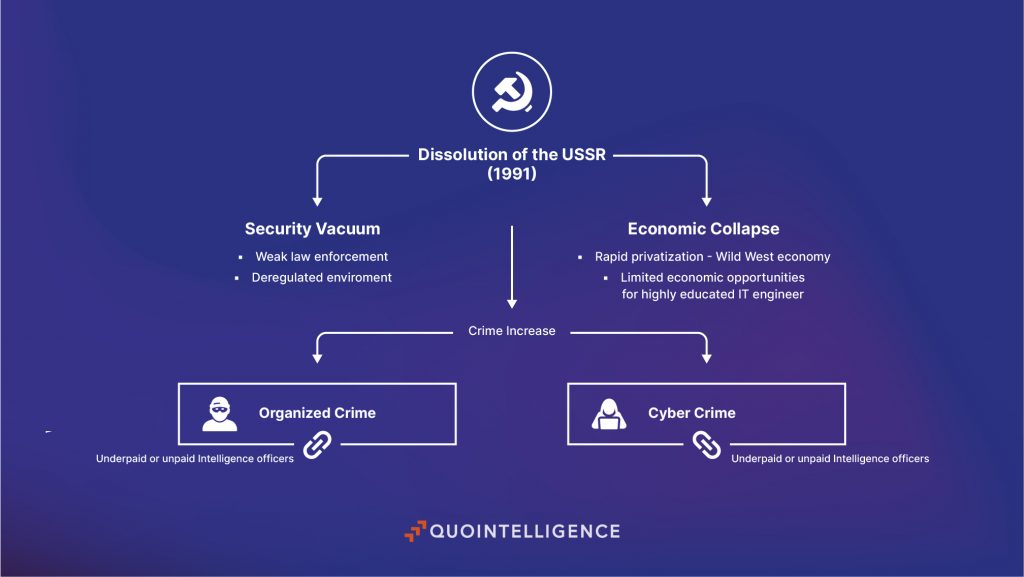

- The collapse of the Soviet Union created a permissive environment for cybercrime, as institutional breakdown and economic hardship led highly trained information technology professionals and former intelligence officers to operate in a gray zone—leveraging their skills in roles that blurred the boundaries between state service, private enterprise, and organized cybercrime.

- Russian intelligence services—the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), and the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU)—operate with overlapping mandates and frequently outsource cyber operations to private firms and criminal groups, enhancing reach and innovation despite risks tied to control and ideological unpredictability.

- Some pro-Russia hacktivist groups such as CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn have coordinated with GRU’s APT44 (aka Sandworm). Similarly, eCrime groups like Conti have cooperated with Russian intelligence service in exchange for protection or tacit approval, but also in some cases out of patriotic sentiment. However, this alignment is fragile; when ideological motivations diverge such cooperation can unravel.

- Private cybersecurity firms provide vulnerability research, tool development, and technical training to Russian intelligence services, while public relations companies lead coordinated influence campaigns, such as the Doppelgänger operation.

Blurring Boundaries: Cybercrime in Post-Soviet Russia

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked a pivotal moment in Russia’s trajectory, laying the groundwork for a unique criminal ecosystem. The disintegration of the central authority created a power vacuum, leaving law enforcement institutions underfunded, and largely ineffective. In this context of institutional weakness, the digital realm was left essentially unregulated, providing fertile ground for the emergence of cyber-related criminal activity. The lack of oversight, combined with a rapidly digitizing global economy, allowed cybercrime to flourish largely unchecked.

This lawlessness was compounded by the economic turmoil that followed the end of the USSR’s centrally planned economy. As the state initiated rapid and chaotic privatization processes, a Wild West-style capitalist environment emerged. The majority of the population faced unemployment, poverty, or limited economic opportunity. Among those affected were highly trained IT specialists. A number of them turned to cybercrime as a lucrative alternative. Similarly, many former intelligence officers, faced with plummeting salaries or unemployment, leveraged their skills and contacts by offering services to flourishing criminal networks. Over time, Russian intelligence agencies began to exploit the informal links that were tied during this period.

Organizational Landscape of Russia’s Cyber Warfare Apparatus

In the Russian strategic worldview, cyber operations, psychological influence, and information warfare are not compartmentalized into distinct categories. They are all viewed as interrelated tools in service of Russia’s foreign policy objectives.

At the institutional level, three principal state entities engage in cyber operations: the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), and the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU):

- As Russia’s main domestic intelligence agency, the FSB is tasked with counterintelligence, law enforcement, and internal security operations. However, its mandate extends to operations in the so-called “near abroad”—the post-Soviet space—where Russia maintains strategic influence.

- The SVR is Russia’s primary external civilian intelligence agency. Its focus lies in the collection of intelligence abroad, particularly in the strategic, economic, and technological domains.

- The GRU is Russia’s military intelligence agency. It is attributed with high-profile cyber incidents, such as the NotPetya malware attack, and is know to use cyber tools to support conventional military objectives.

This institutional ecosystem is shaped by overlapping mandates and bureaucratic rivalries between intelligence agencies. Rather than functioning within a unified command, these services compete for influence and often leading to parallel or uncoordinated cyber initiatives.

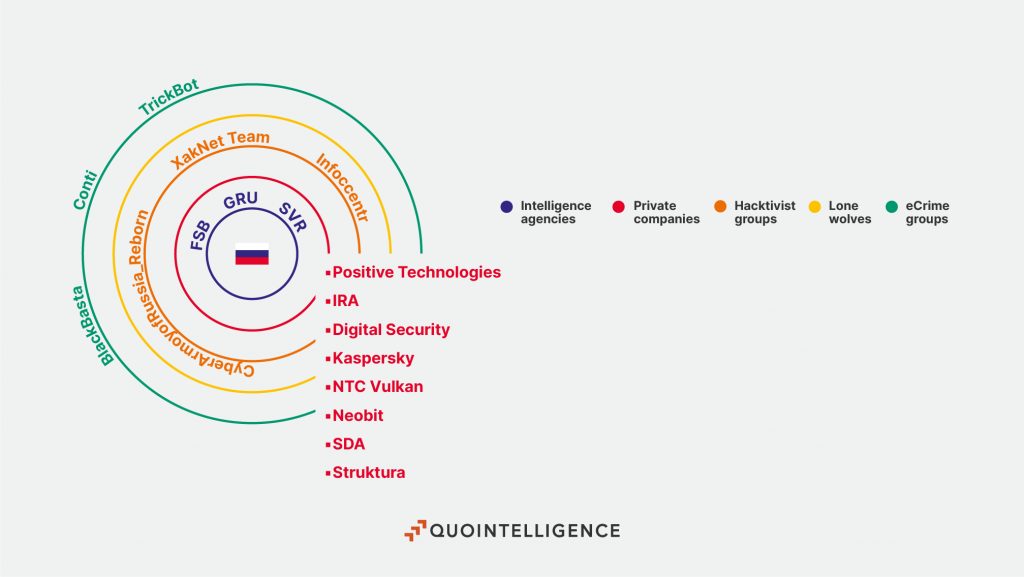

The Concentric Architecture of Russian Cyber Strategy: From State Agencies to Criminal Proxies

Russia’s cyber outsourcing ecosystem is defined by the diversity of non-state actors involved and the fluid relationships forged between them and state intelligence services. It can be represented by concentric rings, with the state in the center, and various types of non-state actors orbiting around it.

Private IT companies form a key pillar of this ecosystem. Russia’s Federal Law No. 40-FZ of 3 April 1995 foresees that enterprises have the legal obligation to assist federal security service bodies in the execution of the duties assigned to these bodies. As such, several companies subject to Russian jurisdiction do cooperate with Russian intelligence services to varying degrees. According to the US, among these companies are prominent industry leaders such as Kaspersky and Positive Technologies. Smaller firms are also tied to the Russian intelligence services such as NTC Vulkan, Neobit, and Digital Security. In addition to IT and cybersecurity firms, certain public relations companies are actively engaged in information operations, such as Struktura, the Social Design Agency (SDA), and the Internet Research Agency (IRA).

Beyond the private sector, Russian intelligence services also exploit hacktivist groups, such as CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn, XakNet Team, and Infoccentr. These groups emerged in the aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. According to Mandiant (now part of Google Cloud), there are likely operational ties between these pro-Russian hacktivists and the GRU, particularly through coordination with APT44 (aka Sandworm). Known joint activity includes destructive wiping attacks against Ukrainian infrastructure attributed to APT44, followed by the public leaking of stolen data by affiliated hacktivist groups in their Telegram channels. These groups are also linked to the manipulation of industrial control systems at water and energy facilities in the US, Poland, and France.

In parallel, Russian intelligence services likely mobilize lone wolves and eCrime groups on a more opportunistic basis. While some actors may be ideologically aligned with Russian interests, others cooperate in exchange for protection or tacit permission to continue financially motivated operations. It is also plausible that individual FSB officers are embedded within these groups to monitor them and eventually influence them. Leaks involving Conti, TrickBot, and BlackBasta have revealed potential links between these groups and the FSB. These ties are likely the results of cultivated relationships with a limited number of individuals operating within this criminal network.

Externalized Capabilities: Private Sector Service Offering in Support of Russian Cyber and Influence Activities

The cyber outsourcing activities conducted by private entities on behalf of Russian intelligence services largely serve a support-oriented role. Rather than leading offensive campaigns directly, these private firms likely provide critical capabilities that enhance the efficiency, scalability, and reach of Russian cyber operations. They supply tools and software platforms used for data collection and analysis, vulnerability identification, and training.

These firms also serve as specialized human resources firms. Through hosting events such as Capture The Flag (CTF) competitions or technical conferences, cybersecurity organizations help identify promising individuals with specialized skill sets for Russian intelligence services to recruit.

When it comes to information operations, private entities play a prominent role in the design, management, and deployment of influence campaigns across multiple digital platforms.

Outsourcing Risk-Benefit: Russia’s Calculated Use of External Cyber Capabilities

Resorting to non-state actors involves both risks and benefits for the state externalizing its cyber capabilities. On the risk side, outsourcing inherently entails a loss of direct control. This is particularly pronounced when engaging non-state actors such as hacktivist groups, lone wolves, or eCrime groups. While collaboration with private IT firms may be formalized through contractual agreements that establish terms and conditions, offering some degree of oversight, engagements with informal actors present greater unpredictability. These actors operate according to their own motivations, and their behavior can deviate from the State’s intended objectives.

Moreover, the motivations of non-state actors are not always aligned with those of the Russian state. Ideological divergence can cause them to withdraw from collaborating. The case of Conti illustrates the volatility of relying on ideologically motivated proxies. In February 2022, the ransomware group publicly declared support for Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. However, this prompted a backlash: just two days later, the Twitter account @ContiLeaks began releasing the group’s internal communications. Although the identity of the person behind the leak remains unconfirmed, some reporting suggests it may have been a Ukrainian or a disillusioned Conti affiliate opposed to the invasion. The resulting fallout led to the group’s fragmentation and eventual dissolution by May 2022.

On the benefit side, outsourcing offers significant strategic advantages. It enables Russian intelligence services to reduce operational costs and maintain flexibility while leveraging the technical sophistication and innovative capacity of external actors. Intelligence agencies, by nature, are structured around institutional knowledge and long-term planning, whereas private-sector experts and underground operators often excel in agility, adaptability, and unconventional thinking. This complementarity enhances Russia’s overall cyber and influence capabilities, sustaining its status as a top-tier cyber power.

One of the most frequently cited advantages of outsourcing in security studies is plausible deniability—the notion that a state can disclaim responsibility for actions carried out by non-state actors, even if those actions are state-directed or coordinated. However, in the Russian context, the relevancy of plausible deniability is limited. Moscow has consistently denied involvement in cyber and influence operations, including those directly attributed to its intelligence services by Western governments and cybersecurity experts. In this environment, the denials are often not intended to be believed, but rather to serve as a form of implausible deniability. This concept refers to the performative denial of responsibility despite overwhelming evidence. It allows Russia to maintain ambiguity, avoid direct escalation, and place its adversaries in a position of uncertainty about how—or whether—to respond.

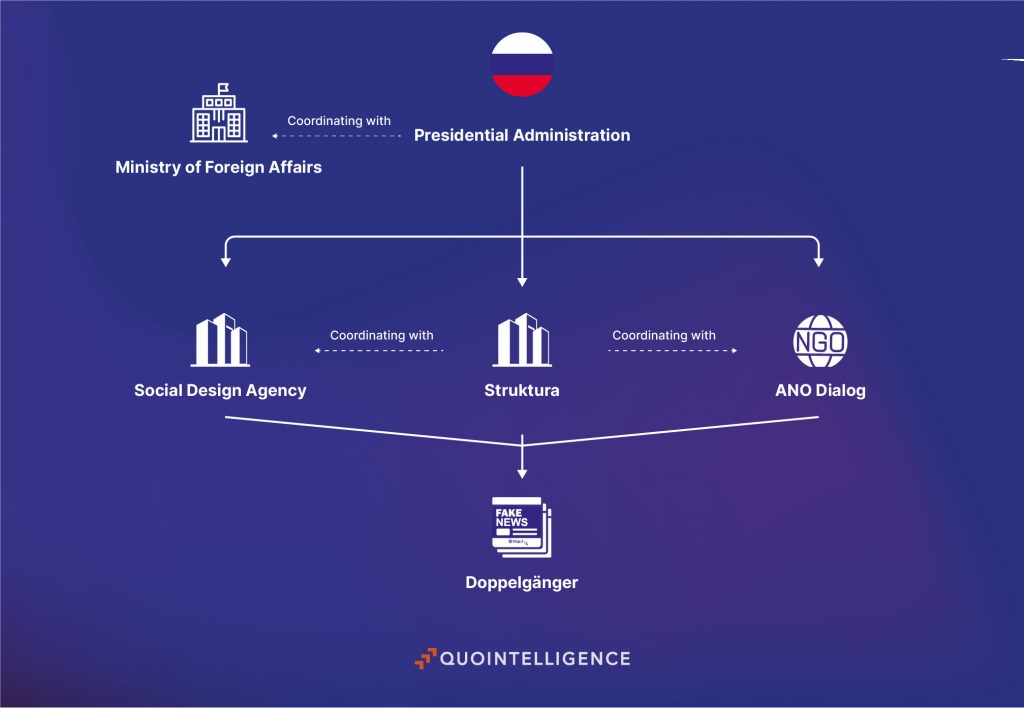

Case Study: Architecture of the Doppelgänger Information Operation Network

Since the outset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, pro-Kremlin influence operations have intensified in both scope and sophistication. One of the most prominent and persistent operation is the Doppelgänger one—a large-scale information operation characterized by the impersonation of legit news outlet and government websites to disseminate disinformation. This operation is executed by a network of Russian companies and non-profit organizations working in close coordination, under supervision from the Kremlin.

The analysis of the SDA leak and the subsequent US indictment reveal that at the strategic level, Russia’s Presidential Administration serves as the command hub for Doppelgänger-related activities. It oversees the funding of these campaigns, issues narrative directives, sets campaign objectives, and collects performance metrics. Members of the Presidential Administration maintain regular coordination meetings with key actors involved in execution. They also liaise with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, leveraging Russian embassies worldwide to relay Doppelgänger narratives, giving disinformation greater reach and an air of legitimacy.

The operational core of the Doppelgänger network is composed of three key entities: the Social Design Agency (SDA), Struktura, and the Autonomous Non-Commercial Organization (ANO) Dialog:

- SDA is at the forefront of the campaign’s execution. It is responsible for both coordination and execution. The agency builds and manages a network of counterfeit websites that mimic official government portals and trusted media outlets across Europe. These fake sites are used to publish false or manipulated content intended to confuse, discredit, or inflame public opinion. SDA also oversees the management of bot farms operating across various social media platforms, enabling artificial amplification and coordinated dissemination of disinformation narratives.

- Struktura operates as the technical backbone of the Doppelgänger operation. Closely linked to SDA—sharing founders, personnel, and infrastructure—it is functionally integrated within SDA’s disinformation apparatus. Struktura specializes in the development and maintenance of the IT infrastructure that supports campaign logistics.

- ANO Dialog, a state-aligned non-profit organization, acts as a vehicle for Kremlin propaganda, promoting regime-approved narratives within Russia at the domestic level.

Taken together, the Doppelgänger campaign exemplifies how Russia leverages private organizations to advance its strategic information warfare objectives.

Conclusions

Russia’s cyber landscape is deeply rooted in the post-Soviet transition, where state weakness, economic upheaval, and institutional fragmentation fostered a breeding ground for cyber criminality. Over the years, this environment has matured into a deliberately cultivated hybrid ecosystem.

This model has enabled Russia to externalize costs, diversify capabilities, and maintain a strategic advantage in cyberspace. The porous boundary between state and non-state actors is not a symptom of poor governance but a deliberate feature of Russian cyber strategy aligning with Moscow’s broader approach to asymmetric competition with the West.

The Russian state’s reliance on this diffuse network of proxies also reflects a uniquely Russian doctrine of “information confrontation,” which treats cyber operations, psychological manipulation, and influence campaigns as part of an integrated continuum.

This fusion ensures that Russia will highly likely remain a advanced and disruptive actor in the cyber domain in the long term.